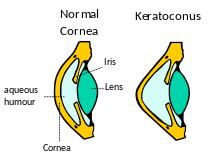

Keratoconus is a condition of conical corneal shape where an irregularly shaped cornea prevents light from focusing correctly on the retina at the back of the eye. In keratoconus, the normally round cornea becomes thin and more cone-shaped, causing blurred vision and sensitivity to bright lights.

What Causes Keratoconus?

There is no known cause for keratoconus, although experts have theorized many causes, including pre-existing medical conditions, heredity, allergies, and eye rubbing. It is a gradual, slow moving disease, which typically starts in the late teens to early twenties and may continue for several years.

Symptoms of Keratoconus

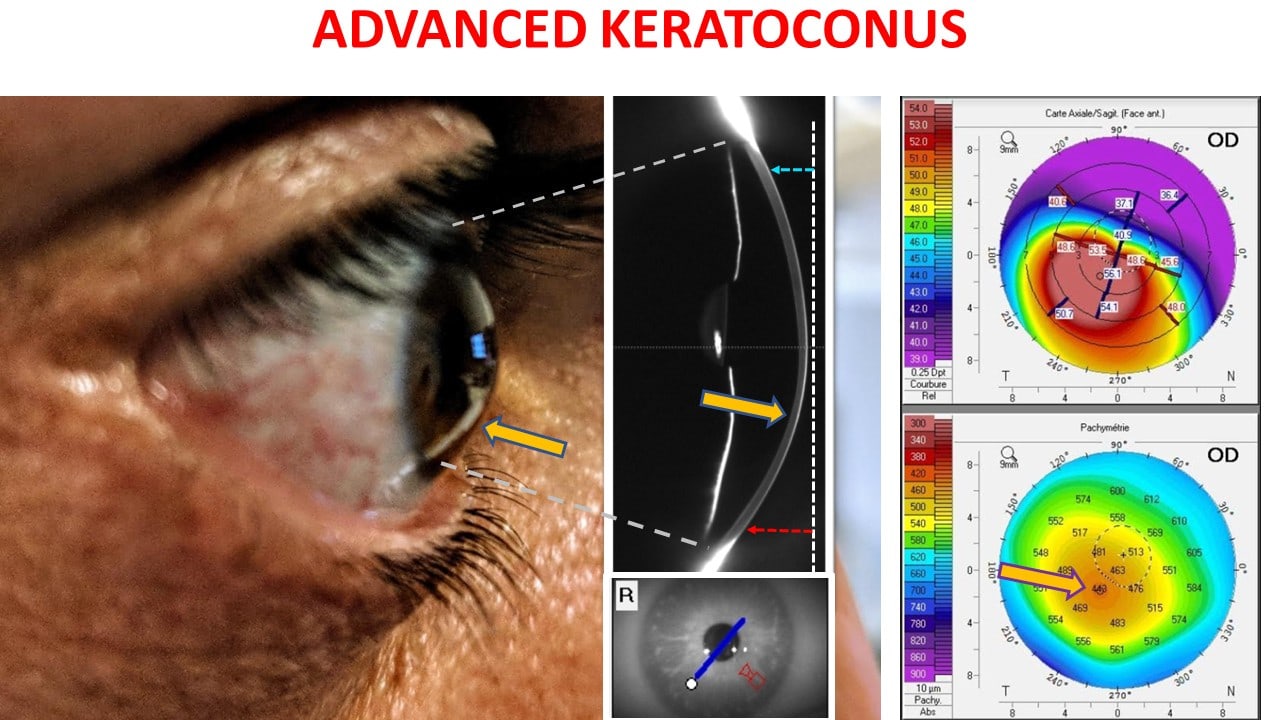

In the early stages, keratoconus causes slightly blurred vision and increased sensitivity to bright lights. As it progresses (over 10 to 20 years), vision may become more and more distorted.

An eye care professional can determine the presence of keratoconus using a slit lamp evaluation or by examining the surface of the cornea through corneal topography.

Symptoms of keratoconus include:

- Distorted vision at all distances

- “Ghost” images – the appearance of several images when looking at one object

- Poor night vision

- Light sensitivity

- Eye strain

- Noticeably worse vision in one eye

- Double vision in one eye

How does it occur?

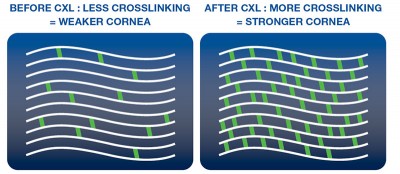

The collagen fibres in your cornea are normally arranged in layers and each layer runs across the cornea in a different direction, in such a way to maximise its strength. This is similar to plywood.

When weakened by keratoconus, these layers can slip, allowing the shape of the cornea to distort and results in a gradual blurring of vision.

How is keratoconus treated?

People who suffer from keratoconus usually require glasses or hard/rigid contact lenses to treat their blurry vision. However, if your keratoconus is severe glasses may not provide a good quality vision and if you suffer from allergies or dry eyes, contact lens wear can become problematic.

Glasses and contact lenses seek to address the blurring of the vision experienced by those with keratoconus but neither of these treatments directly addresses the cause of the problem: the weakness in the cornea. Cross linking typically increases corneal strength by up to 300%.

How can Corneal Cross-Linking (CXL) help?

Corneal Cross-Linking (CXL), also known as “corneal collagen cross-linking”, strengthens the corneal fibres and can prevent further weakening. In reinforcing the structure of the cornea, research has shown that vision can be stabilized although significant improvement in vision is limited.

How does Corneal Cross-Linking work (CXL)?

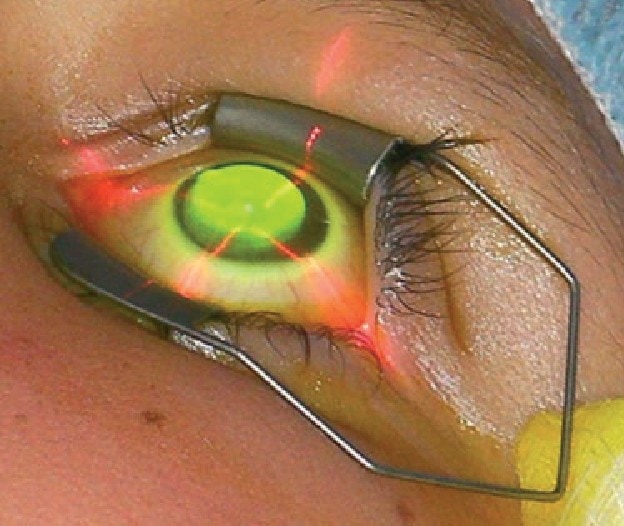

These are several methods used by surgeons performing CXL. In all treatments, UV light is combined with riboflavin (Vitamin B2) to strengthen the cornea.

A solution of riboflavin is soaked onto the eye for several minutes before the cornea is exposed to a low intensity UV light source. The resultant photochemical reaction that occurs during this process strengthens the collagen fibres within the cornea.

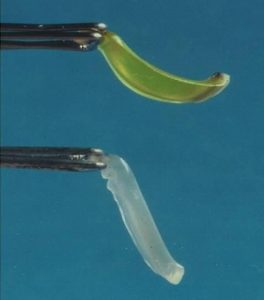

Standard epithelium-off CXL was the original technique. The surface (epithelium) of the cornea is removed prior to the riboflavin being applied to allow deeper penetration of the Riboflavin.

This process requires 30 minutes of drops then 30 minutes of UV treatment. The eye heals over the following week.

At Perth Laser Vision, Dr McGeorge performs 2 types of CXL treatments depending on your individual needs:

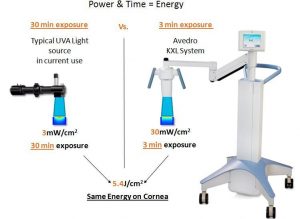

- Accelerated cross-linking with Avedro KXL System

This procedure is much the same as standard epithelium-off CXL except it uses a higher powered UV light for a shorter period of time. By minimising the UV treatment time to only 3 minutes, patient comfort can be maximised and anxiety reduced. Riboflavin soaking time is also shorter. - Trans epithelial CXL

This technique involves keeping the surface layer (epithelium) of the cornea in place while the riboflavin and UV light are applied.

Who invented this treatment and how long has it been going?

Dr Theo Seiler, MD, Professor of Ophthalmology at Dresden Technical University in Germany, was in the dental chair when his dentist told him of cross-linking of tooth fillings with blue light in order to harden them. In a moment of inspiration he conceived the idea of corneal cross-linking for weakened corneas.

He worked with a team of scientists to develop the technique and the first CXL treatment was performed in 1998.

The first publication of his results came in 2003. Twenty three eyes with progressive keratoconus were treated with CXL. The results were positive: in all cases, the keratoconus progression stopped, the corneas flattened, and vision actually improved.

This landmark study was the first of many more comprehensive studies to follow. Since then, results of similar such studies have shown positive outcomes.